“Not a Port that Didn’t Know ‘Em”

Merchant Shipbuilding in Nineteenth Century Toronto

Iain Lockhart

Toronto - 2023

They are gone, yes gone forever, And the rugged roads they travelled, But the wakes they left behind will never fade: Not a port that didn’t know ‘em, As up and down the lakes they plied their trade. Now the lakes are just a highway For the plodding bluff bowed freighters... Though steel and steam is master Still my love’s the fore-’n’-after1

This poem, titled “Windjammers,” was read aloud by Reverend P.F. Garner at a mariner’s service outside of Toronto on April 19th, 1936. Its author, S.A. Clarke, is described as “an old Prince Edward County boy, with a particularly soft spot in his heart for Milford and Black Creek.”2 Clarke’s words paint a nostalgic eulogy for days of sail gone by. Toronto’s shipbuilding was at the heart of Great Lakes tradition, producing a great number of ships throughout the 19th century and beyond. As the 19th century progressed, the nature of Toronto’s marine industry experienced significant change, yet still had much progress to make by the turn of the 20th century in utilizing modern materials and components. Despite the smaller size of its marine industry compared to other Canadian shipbuilding hubs, Toronto’s industries created a diverse array of ships which served to fuel regional transport, trade, and even the construction of Toronto itself.

Initial appraisals of Toronto’s prospects as a site for shipbuilding were skeptical. The shallow depth of its entrance was cause for the Town of York to be disregarded as a shipbuilding location during the city’s earliest days of military shipbuilding. Lt. Colonel Ralph Bruyeres, a Royal Engineer, noted that Toronto was “totally incompetent,” pushing for Kingston to be selected as a site of shipbuilding for the Royal Navy instead.3 Despite Kingston’s deeper waters, its proximity to American territory ensured that the selection between it and York would remain a topic of debate leading up to the war.

Although York was not favoured for shipbuilding, the growing conflict with the United States by 1812 necessitated an increase in local naval power. The first ships built in what would become Toronto were for military purposes rather than merchant ventures. Among the earliest was the 1799 Toronto Yacht, an armed schooner built at York by civilian builder John Dennis but hired as a military transport and employed in carrying government officials.4 By 1812, she was broken up in York, and her materials used to construct another schooner. In January 1812, Captain Gray, the Assistant Quartermaster General, argued that “There is every inducement to build a new schooner at York, as . . . the Toronto having been broken up here furnishes an immediate supply of ironwork and a variety of other articles.”5 From its remains, the schooner Prince Regent was constructed, another early Toronto warship which saw service against the American fleet, including a notable capture of several enemy warships and transports in June 1813.6 The urgency of war with the United States and the immediate presence of material resulted in Toronto’s earliest shipbuilding being of a military nature.

After the War of 1812 ended and peace returned to Lake Ontario, shipbuilding in York quieted down for much of the following decade, reflecting the remaining tensions and trade barriers which impeded Great Lakes trade with the United States. Moir notes that the Merchants Shipyard, located to the east of the town and present in an 1813 map, was absent in the subsequent survey done by George Philpott in 1818.7 Moir does add, however, that “commercial shipbuilding reappeared on the waterfront as the military rationale for the town gave way to prosperity based on maritime trade.”8Additionally, the postwar transition from the Provincial Marine to direct Royal Navy control resulted in many former Marine captains switching to commercial vessels, anticipating the rebirth of merchant activity in Toronto and its trading partners. 9

Figure 1, mapped by Henry Bayfield in 1816 and published in 1828, shows the beginnings of Toronto’s waterfront as a place for trade, and for the docking and construction of ships. 10 Signifying the ongoing transition from military to merchant ports, the two named wharves, Queen’s Wharf and Government Wharf, were for government and military uses.

The Thunder Bay Research Collection, housed by the Alpena County George N. Fletcher Library, reflects Moir’s observation of a revival of maritime trade, as over a dozen vessels were built in Toronto between 1816 and 1824.11 These include the 60-ton schooner Duke of Richmond, built in 1820 by R. Oates. She sank in 1826 yet survived in the form of a rocking chair fashioned from parts of her wood construction.12 Another was the Toronto, a massive 200-ton steamer built in 1824 and described as being “…structurally weak; difficult to keep dry; hard to keep on course; grounded on numerous occasions.”13 Despite this, she was exceptionally long-lived, sailing for nearly sixty years before being auctioned off in 1880.

Toronto’s shipbuilding revolved largely around smaller vessels bound for trading activity within the Great Lakes. Of the ships constructed in Toronto, only six are listed as above 500 tons, for instance.14 Yet at the same time, ships built in Toronto could not be too small. The conditions on Lake Ontario demanded caution, such that Survey General John Collins recommended vessels sailing on the lake be of 80-100+ tons, as he wrote in 1788, “Gales of wind or squalls rise suddenly upon the lakes… Schooners should perhaps have the preference as being rather safer than sloops.”15 Ships built at Toronto’s docks needed to be adequately sized to face the averse weather presented by the lakes they sailed.

Reflecting Collins’ precaution, schooners emerged as perhaps the most common ship produced in Toronto’s yards. The Thunder Bay Research Collection highlights over thirty schooners built in the nineteenth century, while a sole sloop, the 1842 Jenny Lind, is included. Fourteen of these were among those cited by Moir as being built between 1832 and 1855.16 Ford corroborates this preference, noting that schooners entering Niagara outnumbered square-rigged brigs at a rate of eight to one leading up to the War of 1812.17 Schooners remained a preferred vessel throughout the century, as well. Townsend proposes that, according to the Thomas Register, there were 424 schooners and 17 sloops out of the 681 vessels sailing the Great Lakes in 1864.18 Toronto’s own shipbuilding reflected the larger trend of vessel use in the Great Lakes.

By the 1830s, merchant trade began to flourish, with several new vessels being constructed in Toronto’s shipyards. Opinion of the city’s shipbuilding potential was also shifting, an 1834 Commissioner’s Report, in exposing the dire state of the port facilities, urged that the city “secure to the country the best yet most perishable harbour on Lake Ontario.”19 Likewise, an 1833 inquiry by future harbourmaster Hugh Richardson argues that “Of the four (ports), that of York... possessing more of the natural properties of a good harbour than any of the rest (having besides its splendid bason) ...is the only one approaching the verge of ruin.”20 He argues that the maintenance of the port was a public duty, that ”Its local interest is so merged in the public good, that it cannot suffer without inflicting a public injury.”21 In a reversal of perception, the value of Toronto as a port and shipbuilding site was now being acknowledged.

Toronto’s advantageous geography was again praised by Edward M. Hodder in his 1857 study of Lake Ontario ports, among which he claimed Toronto the most promising: “This spacious anchorage is without doubt the best natural harbour on Lake Ontario. It is nearly circular… thus is enclosed a beautiful basin of about two and a half miles in diameter, capable of containing a great number of vessels.”22 Reflecting Richardson’s cautions, he also observes the “extreme narrowness of this passage” into the harbour, and that “heavily laden vessels often find it difficult, sometimes impossible, to beat in or out against a head wind.”23 Although the harbour provided a challenge in accessibility, and needed repair, Toronto’s reputation as a place of trade and commerce grew with its shipbuilding.

Reflecting its growing reputation as a port, Moir finds that the number of ships made in Toronto from 1832-1855 was “comparable to the output of yards in Kingston and Montreal,”24 showing that Toronto indeed had potential for constructing ships as the city and its industry expanded, even challenging other shipbuilding cities. Its position in western Lake Ontario grew increasingly valuable for trade; settlement west had increased over the early nineteenth century, shifting trade with it. Ford argues that “by circa 1840 Toronto was a force in lake commerce… because it successfully combined land and lake steam transportation, forming a good terminus for rail transfers to steamships,” all of which resulted in Toronto thriving in trade through the 1840s.25

Toronto’s developing transportation lines, connecting railroads and steamships, is certainly reflected in the growing production of passenger ships and ferries produced in the latter half of the 19th century. It is telling that, of the corporations listed by name as owning a vessel in the Thunder Bay Research Collection, the Toronto Ferry Company, active from the 1880s, is by far the most persistent. The company accounts for the ownership of at least nine vessels built in Toronto, the earliest being the A.J Tymon, built in 1872 and bought by the company in 1908, renaming it Jasmine.26 Perhaps the longest lived of the Ferry Company’s vessels was the Primrose, built as a steel ferry by John Doty in 1890 (figure 2).27 She served as a ferry from 1899 until 1939 with the Company, then sold and converted to a barge, continuing to work in that role into the 1950s.28 The prevalence of the Toronto Ferry Company and its ships in record reflect Toronto’s growing position as a transportation hub as the century progressed.

Though Clarke lamented the domination of “steel and steam,” which had certainly cemented itself by the time of writing, the transition away from tradition in the Great Lakes was only just beginning as the nineteenth century closed.29 Canadian shipbuilding may have appeared to be entering a new era with the Manitoba, launched in Owen Sound in 1889, as the first large steel ship built in Canada. Yet its construction would turn out to be “an anomaly,” and Wilson argues that Canadian steel shipbuilding, including that in Toronto, “languished, remaining more a hopeful idea than a reality until the first decade of the (twentieth) century.”30 The Manitoba was built by the Polson Iron Works under naval designer W.E. Redway, who acknowledged the difficulty in Canadian steel ship production. He stressed that steel material for the hull was not the issue, but rather the “myriad of internal parts,” in his own words explaining that a steel ship “contains within herself probably a greater diversity of manufactured materials than any other structure.”31 As the National System of protective tariffs dominated Canadian economics in the late nineteenth century, the high price of importing these various parts from the United States or Britain would prohibit the large-scale creation of such ships until the twentieth century.32 Toronto’s shipbuilding, like the rest of Canada, would not fully embrace steel ships until after the 19th century.

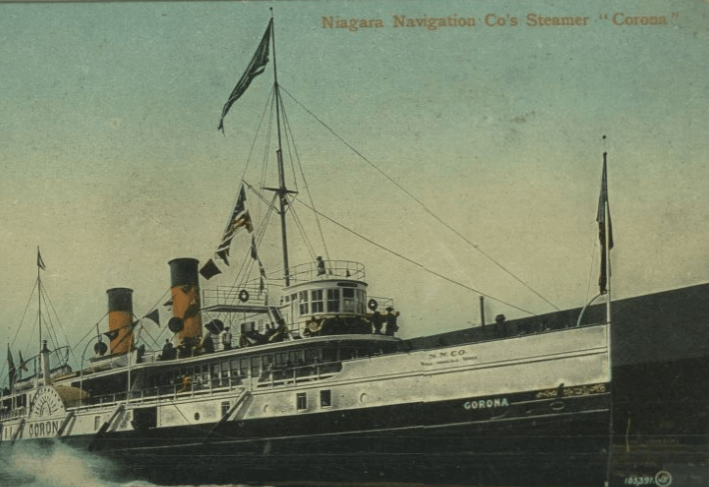

Until that time, wooden hulls remained popular. The difficulty Canada faced in large, steel ship production is reflected in Toronto’s own output of such vessels, which also largely languished until the closing years of the 19th century. The Thunder Bay Research Collection accounts for only nine steel vessels built in Toronto: of which, only four – the Garden City, Minto, Corona, and Toronto – exceeded 500 tons.33 With economic conditions prohibitive to the large-scale construction of steel ships, wooden ships would remain the mainstay of Toronto’s shipbuilding throughout the 19th century.

Redway himself was a notable builder: his company, Toronto-based Polson Iron Works, is credited with several ships launched in the late decades of the century. The company maintains a prolific presence in the Thunder Bay Research Collection, with eleven recorded ships built in Toronto from 1886 to 1889.34 Like the Manitoba, many of Polson’s ships would sail in the waters in Northwestern Ontario. The tugboat Undine, built by Polson in 1889, was used by a lumber company in Fort William from 1910. The 38-ton yacht Mocking Bird made ferry runs out of Port Arthur, today part of Thunder Bay (figure 3).35 Both were constructed by Polson in Toronto, while sailing further north along Thunder Bay.

Another significant Toronto builder was the Bertram Iron Works, which would push the boundaries of Toronto shipbuilding with the largest ships documented in the Thunder Bay Research Collection. The Corona and Toronto, at 1193 and 2779 tons respectively, launched in the late 1890s.36 In Wilson’s words, ships of this size and material truly were anomalies; they resemble the steel ships of the next century far more than the wooden vessels they share the nineteenth century with (figure 4).37

Toronto’s 19th century merchant shipbuilding demonstrated a terrific diversity of vessel materials and sizes. The humble beginnings of military construction gave way to a thriving merchant industry which grew as the city expanded into a major transportation and industrial hub. With the large-scale implementation of steel construction impeded by the National System and high component costs, wooden ships were the mainstay of Toronto’s shipbuilding industry. The domination of steel and steam as lamented by Clarke would not come in this century, but in the next: wartime production and the city’s continued growth allowed Toronto’s shipbuilding to continue expanding. Reminiscing on the sail ships of his youth, Clarke asserted that “the wakes they left behind will never fade,” and likewise, the trail blazed by Toronto’s 19th century shipbuilding led directly into the prosperity and innovation of the 20th.38 The expansion of shipbuilding and the early construction of steel vessels paved the way for “plodding bluff bowed freighters” to sail the Great Lakes throughout the 20th century and beyond.39

-

Robert B. Townsend, Tales from the Great Lakes: Based on C.H.J Snider’s “Schooner Days” (Toronto: Dundurn, 1995): 30. ↩

-

Townsend, Tales from the Great Lakes, 30. ↩

-

Michael Moir, “From Feast to Famine: Shipbuilding and the 1912 Waterfront Development Plan,” in Reshaping Toronto’s Waterfront, ed. Gene Desfor and Jennifer Laidley (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011), 99. ↩

-

C.H.J Snider, “Who Built ‘Prince Regent’ and What Did She Do? Schooner Days 224” (Toronto: Toronto Telegram, 25 January 1936). https://images.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/123242/data ↩

-

Snider, “Who Built ‘Prince Regent’ and What Did She Do?” ↩

-

Snider, “Who Built ‘Prince Regent’ and What Did She Do?” ↩

-

Moir, “Shipbuilding and the 1912 Waterfront Development Plan,” 99. ↩

-

Moir, “Shipbuilding and the 1912 Waterfront Development Plan,” 99. ↩

-

Benjamin Ford, The Shore is a Bridge: The Maritime Cultural Landscape of Lake Ontario (College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2018): 76. ↩

-

Figure 1 – Map of Toronto’s waterfront. Henry W. Bayfield, Surveyor: Henry W. Bayfield, George D. Cranfield, and J. Walker, “Plan of Toronto Harbour, Lake Ontario,” (London: Hydrographical Office of the Admiralty, 1828.) https://images.maritimehistoryofthegreatlakes.ca/122576/image/107621?n=4 ↩

-

“Results: Ships Built: Toronto from 1800 to 1899.” 2022. Greatlakeships.Org. ↩

-

“Results: Ships Built: Toronto from 1800 to 1899.” ↩

-

“Results: Ships Built: Toronto from 1800 to 1899.” ↩

-

“Results: Ships Built: Toronto from 1800 to 1899.” ↩

-

Garth Wilson, A History of Shipbuilding and Naval Architecture in Canada (Ottawa: National Museum of Science and Technology, 1994): 30. ↩

-

Moir, “Shipbuilding and the 1912 Waterfront Development Plan,” 99. ↩

-

Ford, The Shore is a Bridge, 72-73. ↩

-

Townsend, Tales from the Great Lakes, 29. ↩

-

Michael Moir, “Planning for Change: Harbour Commissions, Civil Engineers, and Large-Scale Manipulation of Nature,” in Reshaping Toronto’s Waterfront, ed. Gene Desfor and Jennifer Laidley (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011), 28. ↩

-

Hugh Richardson, York Harbor (R. Standon, 1833): 5. ↩

-

Richardson, York Harbour, 16. ↩

-

Edward M. Hodder, Harbours and Ports of Lake Ontario in a Series of Charts (Toronto: Maclear & Co, 1857), https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.44950/1 ↩

-

Hodder, Harbours and Ports of Lake Ontario. ↩

-

Moir, “Shipbuilding and the 1912 Waterfront Development Plan,” 99. ↩

-

Ford, The Shore is a Bridge, 80. ↩

-

“Results: Ships Built: Toronto from 1800 to 1899.” ↩

-

Figure 2: The Primrose during its service for the Toronto Ferry Co. “View: Primrose (1890, Ferry).” 2023. Greatlakeships.Org. https://greatlakeships.org/2895163/image/2216015?n=111 ↩

-

“Results: Ships Built: Toronto from 1800 to 1899.” ↩

-

Townsend, Tales from the Great Lakes, 30. ↩

-

Wilson, A History of Shipbuilding and Naval Architecture in Canada, 47. ↩

-

Wilson, A History of Shipbuilding and Naval Architecture in Canada, 47. ↩

-

Wilson, A History of Shipbuilding and Naval Architecture in Canada, 47. ↩

-

“Results: Ships Built: Toronto from 1800 to 1899.” ↩

-

“Results: Ships Built: Toronto from 1800 to 1899.” ↩

-

Figure 3: The Mocking Bird. “View: Mocking Bird (1886, Yacht).” 2023. Greatlakeships.Org. https://greatlakeships.org/2902732/image/2213457?n=99. ↩

-

“Results: Ships Built: Toronto from 1800 to 1899.” ↩

-

Figure 4: The Corona. "Corona (1896)". 2023. Greatlakeships.Org. https://greatlakeships.org/2895444/data?n=38. ↩

-

Townsend, Tales from the Great Lakes, 30. ↩

-

Townsend, Tales from the Great Lakes, 30. ↩